Forty years ago, Loughgiel won their historic first All-Ireland hurling title. At the heart of their team was PJ O’Mullan snr at full-back and captain Niall Patterson between the posts. Michael McMullan went to meet them. Here is the story…

LOUGHGIEL is buzzing. The tea, scones and hurling chat are all in full flow. Carl and Karen McCormick roll out a warm welcome.

Photographer John ‘Curly’ McIlwaine is on site to capture the Shamrocks’ build-up to Sunday’s decider with Cushendall.

It’s a typical autumn club scene. October means championship and hopes of glory.

Upstairs, the senior hurlers are gathered. There are 10 days to go. The Dunloy victory has been dissected and they’ve another roadblock to negotiate.

From up the road, the new lights beam down on their training facility. The camogs are honing their touch.

When it’s time, they swap. The hurlers head for the outdoors and it’s the camogs’ slot for upstairs. It’s a clockwork operation.

Over the mugs of tea, Niall Patterson and PJ O’Mullan snr, mainstays from their 1983 All-Ireland team, are energised by a new-look senior hurling team.

Will they win on Sunday? Maybe they will, maybe they won’t. Either way, PJ feels the current team have the tools to challenge for the biggest prize some day at Croke Park.

Niall nods his head. They need backing from the community and if they are lucky enough to dance on the biggest stage, they’ll believe they can write the third chapter of the club’s All-Ireland story.

It’s a story that began over 40 years ago, with the Volunteer Cup’s previous visit a distant memory from 1971.

Loughgiel still lament 1969 and having three goals disallowed in a semi-final defeat at the hands of eventual winners St John’s.

It robbed the Shamrocks of the chance to have six-in-a-row stamped in their illustrious roll of honour.

Like all winners, in any sport, they always pick the bones of those that got away. O’Mullan, sharp as a tack, also files 1974 in the regret column.

Six weeks before the championship, they played Sarsfields in the aptly named Bear Pit.

It was the west Belfast venue where you could’ve had lumps cut out of you in the game, yet fed and watered you like their own in the clubhouse afterwards.

“Gerry McGarry, God rest him, was full-back and got sent off before the ball was threw in,” O’Mullan uttered, like it was yesterday.

Loughgiel still hurled them off the pitch, winning by double scores. The championship final was a role reversal. A Sarsfields man was shown the line before half-time but they still eked out a win.

In O’Mullan’s book, it was one that got away. The false sense of security of the extra man eroded the psyche.

“We should’ve won that ’74 one,” he insists. The ’62 one got away as well.

After their ’63 title, Loughgiel pucked another one away 12 months later in the decider against Ballycastle. They trailed 0-7 to 0-1 with the coastal Glenariffe elements at their back for the second half.

“We turned around and got beat 0-9 to 0-7 when we had a gale force wind, and I mean it was a gale force wind,” O’Mullan recalls. “We hit wide after wide, free after free…we hit them wide. It was one that got away.”

***

For the decade before Loughgiel started their All-Ireland crusade, their 1974 final defeat was a drop in the ocean. Their closest run.

Ballycastle, with four, and Rossa shared seven titles. Cushendall, St John’s and Sarsfields were also champions.

Loughgiel might still have been competitive, but they were in transition. Those who didn’t hang up the boots after ’71 were getting up in years and there wasn’t the conveyor belt the club has purring along now.

SKIPPER…Loughgiel’s 1983 All-Ireland winning captain Niall Patterson pictured at the recording of the latest edition of the Gaelic Lives podcast to mark 40 years since the club’s first All-Ireland win. Picture: John McIlwaine

“The first time I played hurling for Loughgiel, I was 14 years of age and they had just started a north Antrim u-16 hurling league,” O’Mullan said of his early days.

His uncle Nicky and Danny McMullan had arrangements to lift him for a game in Cushendun.

Afterwards, Niall Patterson snr asked him to stay kitted out as a sub for the minor game that followed. And so a career in red and white began.

Living in Cloughmills, Niall Patterson snr and Danny McMullan would’ve arranged to get him to training. There’d be spins on the bike to training.

“I remember going to stay in Granny’s (McGarry) in Carnamena,” O’Mullan continued.

Out to McKay’s field, with his cousins Patsy, Seamus and Martin McGarry, PJ remembers the hours of hurling. The Reids and McAllisters were in the thick of it too.

“You played hurling, you played ‘til dark and you used coats for goalposts,” he added.

Fast forward to Loughgiel training and Niall Patterson jnr has memories of helping coordinate sets of car lights to be turned on to give enough illumination to facilitate the tail end of a training session.

There were also nights up in the Pound Bar after training when the craic would be ninety and it didn’t end at closing time.

“The next thing, Liam (McGarry), God rest him, he’d get us into the house and sit to three or four in the morning watching matches,” Patterson said.

And that was every week. Cork versus Tipperary or Kilkenny versus Wexford. It could’ve been anything.

It was the good old days. Hurling was a religion and everything else could wait.

CELEBRATION TIME…A toast for the 1983 All-Ireland champions in The Poun Bar

Patterson remembers Liam pulling up as he drove through Cloughmills one day with Olcan McFetridge and Bobby McIlhatton already in the car.

A hastily arranged mystery tour was arranged. Not like nowadays when every journey was planned.

Patterson jumped in and it wasn’t until they were the guts of 20 minutes on the road that Carlow was offered up as a destination for an All-Ireland club game.

“We drove along and there was chat, chat, chat and it was hurling the whole time,” Patterson said.

As they got close to the pitch, a blanket of flog descended. Even the end of the car bonnet was out of view.

The match had been cancelled earlier in the day but McGarry’s carload were none the wiser. With the craic and banter, they were oblvious to the radio bulletins.

Ach, sure there was bound to be a match on in Croke Park. And off they went.

“We sailed to Dublin…Cavan were playing Dublin in the football, so we went to it,” Patterson continued of their impulsive foray south.

With parking spaces at a premium, Liam sold the Garda the story of having two Antrim hurlers in the car and he’d do them a deal.

A parking spot in exchange for throwing them “a couple of sticks” the next time he was down. It worked and the Guards kept an eye on their car.

“That’s the way Liam worked, he could’ve have gone anywhere,” Patterson said.

“He was a great club man and wild about hurling. I can remember my Da telling me that Liam wanted to play corner forward at a time.

“Liam McGarry was the best corner back in Ireland at a time and I mean that. You couldn’t tell Liam that, he wanted to get up front.”

***

Loughgiel’s 1983 All-Ireland success story nearly didn’t get past the first page.

A Feis Cup defeat to Glenariffe prompted a brief announcement in the dressing rooms in Glenravel.

Niall Patterson snr, one of the selectors with Dominic Casey and Liam McGarry, said there would be a meeting on Tuesday night. On the agenda would be a threat to pull out of the championship such was the poor performance in the 60 minutes of hurling beforehand.

“He didn’t read the riot act on the night of the game because there probably would’ve been a row,” Patterson jnr recalls of his father’s words.

“He said that if we didn’t want to hurl, we’ll pull the team out of the championship, that’s what was said.

“We had the meeting on the Tuesday night. We came down, trained, had a meeting and cleared the air. There wasn’t much air to be cleared. We just had a disastrous game.”

Another factor contributing to their change of fortunes was an refined attitude towards discipline. Too often Loughgiel players would be fond of leaving the timber on an opponent.

A free won would’ve been met with retaliation and the sliotar would’ve been thrown in.

“We decided that it takes a better man to be hit, set the ball down and walk on,” Patterson said.

“It takes a braver man to do that and that was something that came into our game at that time.

“We worked on the discipline. If anybody got hit, they set the ball down and we got the free. It made an awful difference.”

The opening two championship games were nothing to write home about. O’Mullan recalls missing the St John’s game through injury and how goals from Joe McGurk helped them to victory over both the Johnnies and Sarsfields.

At that point, an All-Ireland title was a dream from another world. Cushendall could’ve washed them away in the semi-final.

Niall Patterson recalls a moment late in the game with Alastair McGuile unmarked on the edge of the Loughgiel square with Dominic McKeegan bearing down on goal.

“All he had to do was handpass the ball into McGuile and we were beat,” Patterson explains of the turning point in front of his eyes.

“Our defence ushered him over the end line and it was a wide ball. To me, the hairs are standing on my arms talking about it. That’s how close it was.”

In the weeks before the final, trainer Danny McMullan went to work on a regime that saw them primed for their showdown with Ballycastle.

“Danny just peaked us at the right time,” Patterson said. “I remember talking to some of the supporters and they knew the way we came out onto the field, there was no way we were going to get beat.”

O’Mullan sets the scene. Ballycastle were Loughgiel’s bogey team and after a string of quarter and semi-final defeats, it was a first final meeting since 1970.

In previous years, a 17-year-old Patterson remembers the ‘you’ll win a championship someday’ hard-luck story followed by the emptiness of further defeats.

This time it was different. The weeks of training left them made for hurling.

“They got two goals at the death,” O’Mullan said of a win over Ballycastle that was more comfortable than the scoreboard suggested.

The growing belief, planted as a seed by the management, was another key ingredient that helped them get their hands on ‘Big Ears’, the biggest prize in Antrim club hurling.

In Ulster, despite winning by 15 points, the Shamrocks endured a physical semi-final afternoon in Clontibret. They were battered.

“Their captain came into the dressing room after the game,” Patterson remembers.

“Antrim champions,” he told them, “youse are an effing disgrace and you boys will do nothing.”

Next up was Ballygalget in the final. On their home pitch, the Down champions were slick enough to force Loughgiel into a tactical outlook.

A refined game plan was new ground. Traditionally, Loughgiel’s mantra rarely deviated from getting fast ball up to their forwards. It was direct and demanded the inside men to deliver the goods.

“We were a great team for ground hurling, first time hurling,” O’Mullan said, comparing it the style the current senior team put to use in their semi-final win over Dunloy.

“There is a whole lot more short passing in the game now,” he added of the lie of hurling’s evolution.

“We still played a lot of fast diagonal ball into the forwards, that’s the way we always played.”

That was all very well, but they were facing into an Ulster defeat in 1983. There was no place for pride.

“We were struggling,” Patterson said. “Somebody in the management team made the decision to take Mick O’Connell out of midfield to act as a sweeper.

“That was unheard of, I think it was the first time a sweeper had been used and it changed the match for us.”

The other half of the move was Eamon Connolly pushing from his wing back role to pick up the next player out the field.

Connolly, better known as ‘the beast’ was laid to rest on Tuesday after cancer took him too soon.

Patterson tells of Connolly’s other alter ego, Charles Manson, because of his big beard.

“The beast was a strong hurler,” O’Mullan said. “He would’ve hit you for the fun of it and did to many a boy.”

Their new tactic decommissioned Ballygalget’s attack that was thriving off Martin Bailie, the Braniffs and the Coulters.

“Charlie Coulter had hands on him…one was bigger than my two,” O’Mullan added. “The very first ball that came in, he nearly broke my neck. A big strong brute of a man.”

Moycarkey-Borris were Loughgiel’s All-Ireland semi-final opponents and had not scored a goal since their drawn Tipperary final with Roscrea.

In the days of the home and away rota, they travelled to Loughgiel.

The night before, Niall Patterson’s music booking took him to Lavey club where James Convery felt that the Munster men would have too much for the Ulster champions.

“They’ll put 10 past you,” Patterson remembers him saying, to which he took a £10 bet he’d keep a clean sheet.

The next day, with just seconds gone, John Flanagan had the Loughgiel net rippling.

“Inside ten seconds, your tenner was gone,” O’Mullan said in laughter.

The Mick O’Connell sweeper role was reset and it was back to the traditional 15 on 15 and survival of the fittest.

“We only conceded a goal because ‘Tart’ (Martin Carey) slipped,” O’Mullan offered. “It was a wet night [the night before the game] and he slipped and I can still see them hitting into the net yet.”

At the other end, Paddy Carey jnr and Aidan McCarry banged in quickfire goals for a 2-7 to 1-6 win, sending Loughgiel to Croke Park.

“It was unreal,” O’Mullan said of the feeling.

“It was great that evening I remember going up into the club.”

There were refreshments for the travelling team and their supporters.

As both clubs mingled, a Tipperary accent asked – looking at O’Mullan – if was one of the players.

“That’s the man with grass on his fingers,” came the Moycarkey-Borris response when told he had been the full back.

“They were on about the one I lifted out of the square,” he laughs. “There was a big scramble and I got it away out.”

A decade later, Patterson was playing in a golf event in Donegal and was playing music in a pub at night when a man introduced himself as John McCormick from the Moycarkey-Borris team in Loughgiel that day.

“You see your full-back, he is a dirty so and so. He said PJ was as tough a man as he had played against,” Patterson recalls with another bout of laughter.

There was another instance when Galway side Castlegar were invited to play at an invitational tournament in Loughgiel.

At the time, clubs were invited from across Ireland with the aim of exposing Loughgiel and the other Antrim clubs.

Part of the social side of it was a dance up in Reid’s barn with upwards on a thousand revellers at it.

At the end of the night, there was a ring circled around with Loughgiel full-back PJ O’Mullan and his Castlegar opposite number Padraig Connolly.

“The two of them went at it, hitting each other with their shoulders to see who was the toughest,” Patterson recalls. “He (PJ) was left standing…as hard as nails.”

Did this strongman contest count as a second All-Ireland Club medal?

“Without a doubt,” he replied in jest.

Invitation matches were part of Loughgiel’s fabric. Len Gaynor was up with his Kilruane McDonagh side, All-Ireland champions in 1986, and told O’Mullan there would be a spot at corner back on the Tipperary team back home such was his display.

Another such game happed in the July of 1983 when Kiltormer of Galway and Loughgiel were invited to the opening on a pitch in Rasharkin.

Kiltormer lost to St Rynagh’s in the All-Ireland semi-final back in February but appealed the game on the strength of Declan Fogarty being sent off and remaining on the pitch for seven minutes.

It held up the All-Ireland series until, after an eight-week gap, Kiltormer’s case was thrown out and there was an April date between St Rynagh’s and Loughgiel.

“It was some game and we beat them,” O’Mullan said proudly, meaning they’d beaten the champions of the other three provinces that year,

“Big Slim (Brendan Laverty) was carried off after 20 minutes and he had seven points scored, it was mighty.”

***

Playing in Croke Park didn’t faze Niall Patterson. A deep thinker, by his own admission, he looked on as the Loughgiel players put the time in playing snooker in Dublin on the eve of their All-Ireland final date with St Rynagh’s.

He’d been there was with Antrim and would have other days at HQ, but there was a deep sense of pride that this was different. This was the boys he’d grown up with.

Even now, sitting in Loughgiel clubrooms 40 years on, the pride is written across Patterson’s face as he talks.

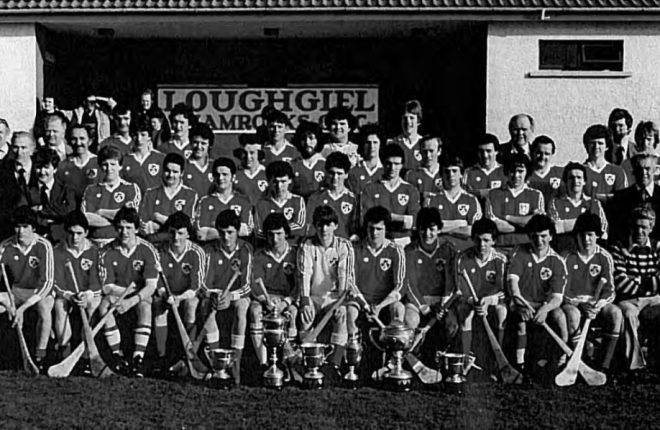

WHEN WE WERE KINGS…Loughgiel’s All-Ireland winning squad of 1983

PJ O’Mullan speaks of the youngest member of the team, Martin Coyle, repeatedly trotting off to the toilet with the nerves.

“He scored a first point of the game after 20 seconds and a fine point it was with the first ball he got, so it settled him down,” O’Mullan said.

Patterson recites a litany of nicknames and their ages, most in the 20 or 21 bracket.

O’Mullan talks about how they had the chances to win only for nerves to kick in at important times and missed chances.

On the flip side, with the sides level – 2-5 to 1-8 – St Rynagh’s had a free to win the game.

“I asked the umpire how long was left,” Patterson remembers of the key moment.

“A minute,” came the reply and Patterson requested a sliotar for an emergency restart in search of an equaliser.

The late St Rynagh’s chance pulled wide and Patterson’s puck-out, belted as long as he could, was greeted with the final whistle.

“If he had put it over the bar, that would’ve been it,” Patterson surmises.

Sitting in the Loughgiel dressing room, he remembers the Moycarkey-Borris management coming in, apologising they’d not get to the replay with a county final being hosted on their ground.

Patterson was asking himself the question. Had they missed the boat? Traditionally the southern teams bounce back and the underdogs usually only get one crack at glory.

“I didn’t say anything, but I had it in the back of my head that we had missed the boat,” he said, again deep in thought.

“Come Tuesday, when we were back training, I had come around and there was no way we were going to be beat.”

Another saving grace was having just a week to get themselves in the zone as opposed to the week on week ‘it is on or not’ saga of the drawn game following ‘Fogarty-gate’ holding up the competition.

“Wee Danny (McMullan) was stuck between the devil and the deep blue sea,” Patterson said, referring to the unknown lead in time.

“The good thing was that before we came out the dressing rooms at Croke Park, we knew the replay was in Casement…it was agreed and all,” O’Mullan added of another plus in Loughgiel’s favour.

The Shamrocks were six points up for most of the second half and would always be able to hit back anytime the Offaly men registered a score.

“It was a fairly frantic match and plenty of first time hurling in it,” O’Mullan said. Patterson agrees, telling of the night in Loughgiel club, when they watched it back.

“I didn’t realise how good a game it was and how fast it was,” he said. “The game has moved on so much, but that game could’ve lived with anything.”

St Rynagh’s bagged a goal from a penalty and were starting their charge back into the game.

“That left three points in it,” Patterson said of the closing stages. “Dermot Devery was coming through on a solo run. ‘The Beast’ was at him, tapping away as he ran with the ball and it went wide.”

Devery was lucky he did. On the inside channel was a revved up PJ O’Mullan, prepared to take man, ball and all. Nothing was going to deny Loughgiel the perfect ending to their eventful season.

Patterson remembers picking up a stray ball late in the game. One he should’ve let trickle over the end line to eat up a few more seconds.

“I’d say it was the furthest I’ve ever hit a ball in my life,” he joked. The venom and purpose nearly carried it wide at the other end.

Then came the sweetest noise of all, the final whistle signalling Loughgiel’s All-Ireland title at last.

After being reared on stories of the teams from the fifties and sixties, they’d made their own history.

Now, 40 years on, Patterson confesses to crying “like a wean” at the club’s 2012 success and counts himself lucky to have experienced both sides – on the pitch and off it.

SAME AGAIN…DD Quinn and Johnny Campbell with the Tommy Moore Cup after Loughgiel’s second All-Ireland title in 2012

“I was secretary of the club,” O’Mullan said of the 2012 success, one his son PJ jnr steered as manager.

He looks back on the Loughgiel dressing room before extra-time in their semi-final with Na Piarsaigh that year, a game he ranks as good a club game as he’d witnesses.

A flat Loughgiel dressing room in Parnell Park was transformed when Jim Nelson’s radiant body language inspired a team to lift themselves one more time and within the space of a few weeks, Loughgiel had a second All-Ireland to their name.

“Jim was up there with all the great coaches,” O’Mullan snr said. “The man who took us in ’83, Danny McMullan, he was the same…was away before his time.”

Patterson agrees. Loughgiel have had great servants and continue to have.

“That’s why we are where are,” O’Mullan adds. “They might not win on Sunday, but I wouldn’t be surprised if that group of players [current Loughgiel senior team] go on and win the All-Ireland.

“There was a while watching it that it would’ve depressed you, but when you see them performing the way they have been performing in the last two matches, yes it’s brilliant. Long may it last and I think it will last.”

And so the cycle continues. Stars of the past chatting about their memories and hope of what is to follow. Part of Loughgiel is about Sunday in Corrigan Park. But it’s only one piece of the jigsaw.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere