Johnny Corvan has been inducted into the Armagh Harps Hall of Fame. The former Armagh star has lived in Australia for almost 40 years and looks back on his career. He spoke with Michael McMullan.

JOHNNY Corvan has lived in Melbourne longer than in Ireland but has always been revered as one of Armagh’s greatest.

When his sister-in-law Carmel Kelly accepted the Phil McGinn trophy last Friday on his behalf, Corvan stepped into the Armagh Harps Hall of Fame. A forever legacy for someone who had helped etch many of their illustrious earlier chapters.

A quick dip into YouTube and the artistry jumps out. A charismatic baller. Check out his inner Marco Van Basten against Cork in Páirc Uí Chaoimh.

Predominantly left -footed, yet well able to turn across to his right, he was also renowned for his nifty chip lift. Add in footballing smarts that steered him not only into space but any vacuum defenders wanted closed off.

Where do you start? His three points and the goal he made for Joe Kernan weren’t enough to quash Kerry’s five-in-a-row hopes in 1982 before Seamus Darby eventually did.

It put Corvan in the conversation that, after another impressive season, earned him an All-Star replacement call the following year. You get the picture. A wizard of a player.

Starting out, while quick to point to the value of the collective, Corvan was Brother Kelly and Jimmy McKeown’s central axis as Armagh CBS won three MacLarnon Cups and two All-Ireland titles.

Scoring all but three points of their 3-10 tally, he sank Bandon’s Hamilton High School at Croke Park. By then he was school captain in his fourth season in the Harps’ senior team.

A hurler with Cuchulainn’s, the wee ball was his first love. His four goals in a blitz of St Mary’s earned Armagh CBS a Mageean title, ending the Belfast school’s monopoly on the competition.

He was three years a county minor. There was regret in his final season, missing out against Down in an Ulster final replay, watching on as they lifted the Tom Markham Cup for the first time in 1977.

There were league finals with Armagh and an Ulster title in 1982. While not picking up a winner’s medal, Corvan was the league’s top scorer. As well as the obvious unpredictable flair, there was repeatability that left him unerring when kicking frees.

As a 15-year-old, he won an intermediate title with the Harps despite it being his first year on the senior team, having not yet played a handful of seasons at underage level. Corvan was special.

FAMILY TIME…Johnny and Ursula Corvan pictured with their children Orlagh and Sean and their partners

These were the days of teak-tough football when another set of eyes would’ve been useful, to see a closing defender’s shadow. Corvan’s feet did the talking. The older hands minded him, swapping across to put manners in anyone attempting to rough him up.

The Harps pressed on to the senior final the following year, only to lose after a replay to Crossmaglen.

Having moved to Australia in 1987, Corvan returned home to be best man at his brother Paul’s wedding four years later. Harps were in the senior final and manager Fr Peter Paul Kerr’s powers of persuasion convinced him to come on board.

Down to 14 men and with Maghery having a grip, Corvan came off the bench. It wasn’t what he had signed up for, having agreed to come in as an experienced head around training, yet here he was.

His vital possessions sucked extra Maghery defenders to him. And there is no substitute for class. He made the point that levelled the game and his fingerprints were over every score they kicked during his time on the field. Each of them golden in a 0-11 to 1-7 victory.

Fr Kerr wasn’t the only one after him. The Brunswick Juventus semi-professional soccer team he played for back in Melbourne lost their penultimate game of the league season.

It was their only defeat, on the day Corvan was by Paul’s side at the altar. Soon the club owner was on the phone, pleading for him to return for the final game.

A return business class ticket and even a few extra quid couldn’t convince him to pass up the Harps’ big Sunday. In the end, it was a good call. Harps and Brunswick both danced in the victory hour.

His late father Sean wasn’t a soccer man. He was staunchly against it but Corvan still managed to tip away for Milford Everton and later Newry Town. There were also schoolboy appearances for Northern Ireland.

A common occurrence was sneaking out the back door with a bag, on the way to a soccer game. Some days his father would catch him and his day was gone.

His talent was enough to land a trial with Glasgow Celtic but he didn’t bite at an offer to go over the water when Liverpool wanted a peek under the bonnet.A trial with Arsenal led to a game with the reserves. Having returned home, manager Terry Neill later showed up on his doorstop in Armagh but Corvan wasn’t interested in joining the Gunners’ growing Irish influx.

Could he have made it as a professional soccer player? That’s the million-dollar unanswered question.

One thing is certain. An hour and a half chatting across a web link with Johnny Corvan is time well spent.

He is just in the door from a round of golf. He watches all things sport and loves talking about it. Facts and memories flow with ease. Football. Hurling. Soccer. Senior and underage. Everything.

A Liverpool fanatic, he reckons he was glued to the live coverage of all but three of their games as they landed title number 20.

The hairs were standing on the back of his neck as his voice was one of over 100,000 belting the club’s anthem, You’ll Never Walk Alone, at the nearby MCG during a recent tour.

Sean Devlin and Sean ‘Dingle’ Daly were Corvan’s childhood heroes growing up in Armagh. Frank McGuigan and Matt Connor were the best players he saw in action. David Clifford is now hot on their heels.

In soccer terms, it was George Best and Kenny Dalglish. Corvan got to play in Best’s Ireland select against Denis Law’s Scottish counterparts in a charity game in Australia.

The Irish were 5-4 winners. Their former Armagh star bagged a hat trick, linking in with Best for all of them.

Watching Corvan’s magical moments and talking with him, you soon get a feel for a genuine love of sport. It was his expressive side. He is also a thinker and reader, often finding himself down a rabbit hole.

On the topic of the FRC and the new Gaelic football rules, he is a fan. He’d love to be playing the game now but the 50-metre advancement needs tweaked.

He is full of praise for fellow county man Jarlath Burns and how he empowered Jim Gavin to draw up the blueprint for change. Corvan would gladly grant Burns another term.

“I don’t mean to be too hard on coaches, but they had taken football to a very, very dark place in my book,” Corvan said.

“Something needed to be done. It’s not perfect now, but it’s a 100 times better than what it used to be.”

The next step would be to look at hurling, its rucks and the other pariah, one that is the bone of contention among many.

“They do need to sort out their handpass, if there is such a thing as a handpass in hurling,” he added. “They’re just throwing the ball.”

The concern of the runaway paid manager also needs addressed and how clubs are operating on fumes. His solution? Draw up a contract, pay them and leave everything out in the open.

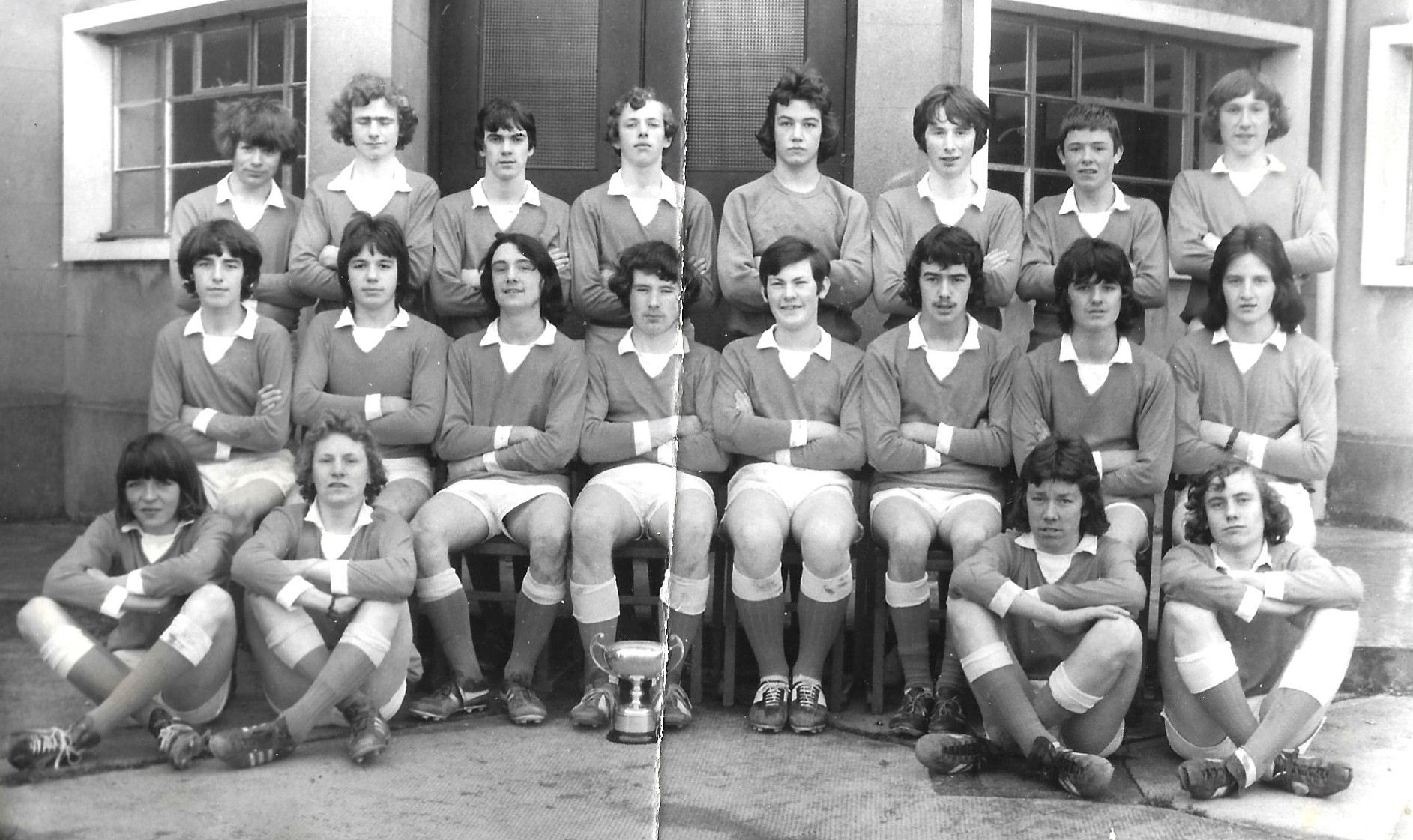

SCHOOL DAYS…Johnny Corvan won Ulster football and hurling medals with Armagh CBS

There is also pride in Corvan’s voice at being added to the club’s Hall of Fame.

“When I was a kid, I used to think the Hall of Fame was for old people,” he said with a smile. “Maybe that says something now.

“When you look at the recipients, they’ve been stalwarts, people that have done a lot for the club. I feel really, really honoured.”

*****

Corvan and the GAA were always going to cross paths. He goes back to looking at a photograph of 1918 Armagh senior champions – Young Irelands, a team in the days before Pearse Óg and Harps.

“One of my grandfathers, Jack O’Brien, was captain of that team and my other grandfather, John Corvan, is sitting beside him,” Corvan recalls.

His Granda Corvan was one of those responsible for getting the Gaelic field up and running, now the site of the BOX-IT Athletic Grounds.

Granda O’Brien was on the cusp of signing for Everton only for a broken leg in a GAA match putting an end to a soccer career over the water before it had even begun.

Corvan’s parents, Sean and Ursula, lived in Clogher where Sean worked in the local butcher shop.

“I was born in Tyrone, but I was in Armagh before I was two,” said Corvan, the second oldest of seven.

The Corvans lived in Windmill, the Ógs end of town. Johnny could peek across at the Athletic Grounds, yards away, from his bedroom window.

“I was probably nine or ten and we had a green at the bottom of the housing estate where we would play football every day,” he recalls. “There’d be competitions between the various housing estates.”

Playing against boys much bigger and older forced Corvan to learn awareness and a speed of thought.

“You just need to learn to move quicker than them,” he said. “I don’t think as much of that happens today.

“I stayed in the home place when I was over last year for a few months and I rarely saw a kid out in the street with a ball of any sort or doing anything out in the street.

“Whereas when we were kids, we were very active. It was a very outdoor lifestyle back then.”

Corvan would’ve been walking around with a hurl and sliotar. Living beside Jimmy Carlisle, Armagh’s ‘Mr Hurling’, rubbed off and Corvan was soon in action with the Cuchulainn’s.

By the age of 12, Corvan was in with the Harps’ u-16 footballers, the club’s youngest team in those days.

His father Sean had been a dual player too. Being from Milford, he played football with Madden. Sean’s wife, Ursula O’Brien, was from the Harps side of town.

For all the football Corvan played, he looks back on the roots within the Harps and those that kept the plates spinning.

It seemed like Joe Mackle coached all the underage teams, making sure everyone had a way of getting to games before logistics was even a word. Bobby Gamble was another who did plenty of the heavy lifting.

In school Brother Kelly and Jimmy McKeown ran the football teams.

With soccer the forbidden sport, Corvan mixed football and hurling all the way through.

With Cuchulainn’s and Keady in the county hurling final every year, it would often clash with the football games with the Harps in the same day, but the clubs had an arrangement.

“The hurlers would often play first,” Corvan remembers. “If I was to play hurling, I had to play in goals.

“I think I won three county finals in goals with the Cuchulainn’s and two out the field, that was the compromise to allow me to play.”

The initial county senior call came in 1977, in his final year with the minors. Gerry O’Neill touched base after their Ulster final disappointment, asking if he’d join the senior squad ahead of the All-Ireland semi-final.

County chairman at the time John O’Reilly didn’t sign off on it and left a disappointed Corvan wondering if he could’ve broken into the senior plans as they reached the All-Ireland final. He’ll never know.

“Training was old school and brutal,” Corvan said of life when he hooked up the following season.

“Gerry would run you until he broke you. I remember January pre-season, running around boggy pitches in Killeavy, in Silverbridge, in Armagh and in Lurgan.

“When you know a little bit about the science now, you think, Christ, how the hell did we survive it?”

Corvan was in and out of squads in the years to come. There was an Ulster title in 1982, sandwiched by league final defeats at the hands of Down and Monaghan.

It was a far cry from where football in the county was in the mid-seventies. Corvan can remember two people being asked to come in from the crowd so they could field the bare 15 for a league game in 1974.

It was a mark of the strides made by O’Neill in steering them to the third Sunday of September three years later.

“It was hard sometimes playing in an Armagh team where I often felt we didn’t play to our full potential,” Corvan states, admitting he was never afraid to speak out.

“County teams are so well organised today, probably too much. We were probably at the other end of the scale.”

With a bit more shape they could’ve added to the 1982 Ulster success but key moments went against them too.

Corvan refers to the ’85 league decider, played in heavy rain, against Monaghan and how Thomas Cassidy was harshly penalised for steps that led to a penalty. Shortly after, Corvan hit a rasper that went over off the bar instead of under it. The fine margins.

Two years earlier, with a peppering of early ball, Corvan and the late Mickey McDonald – uncle of Grand Slam golfer Rory – were putting on a scoring clinic. Armagh then began to shoot on sight, rather than hitting the runs of their deadly duo and Down went home with the cup.

Fr Sean Hegarty came in as manager, steering Armagh to Ulster finals in 1984 and 1987.

“The best thing Sean ever did was bring in Eamonn Coleman,” Corvan said of the man who later led Derry to their only ever All-Ireland, ironically with Hegarty instrumental in Coleman later getting the Derry hotseat.

“Eamonn Coleman turned things around in a really, really good way, it’s a pity he didn’t hang around for a bit longer.”

By the time the 1987 Ulster final came around, Corvan was watching on from the stands after calling time on his inter-county career after the league.

“We had played Monaghan in the National League and I got sent off,” he recalls of his last game.

“Gerry McCarville had been sent off and so the referee was out to even things up.

“Somebody ran past me and did a bit of a swan dive without me being anywhere near them. The referee came over and sent me off.”

With that, two years short of his 30th birthday, Corvan had played his last game on Irish soil. It was time for a new chapter in more ways than one.

*****

The north of Ireland in 1987 wasn’t the easiest place to rear two children and Australia offered opportunities.

“My brother-in-law had come out here previously,” Corvan began on the decision to move ‘Down Under’.

“There was a bit of money playing soccer and there were jobs around. Ursula and I thought it was a really good opportunity for us to go. The kids were seven and eight when we came here.”

With the children settling into their new surroundings, Corvan continued the youth work he was doing back in Ireland. He began to study, had a second job and was playing semi-professional soccer.

After three seasons with Ringwood City, he transferred to Brunswick Juventus for another three.

“The standard was pretty good, probably a little bit higher than the Irish League,” he said. “We had a few Irish League players in the league too.”

In one of his first games, while warming up, “hey, Corvan” came the shout from the opposing team. It was Gerry Clarke who had played for Antrim. Despite being on the other side of the world, the Irish accents soon became more regular.

“The first five years were pretty full on,” he said of their commitment to make Australia their long-term plan.

MISSED CHANCE…Johnny Corvan, far right in back row, pictured ahead of Armagh’s 1985 league final defeat at the hands of Monaghan

“Then I moved into work for the government in public service, so I worked in youth justice with them for 14 years.”

“There were a couple of years working for the Tasmanian government in the middle of that as well.

“Then I worked for the Australian federal government, running a family law court in Victoria and Tasmania.”

Corvan then ran a family law service in Melbourne for the last dozen working years before retirement.

“The thread through it all was working in the justice system, criminal justice, youth justice, and then family law,” he said.

“I enjoyed a lot of it but family law is very tough. I still see a lot of people that I’ve worked with but we’re all that age now, we’re all getting out of it. I am retired the last couple of years and have been thinking how Australia has been very good to us, but we’ve worked hard.”

After spending time playing soccer and working to help settle in, Corvan then found time to lever GAA into his world again with Melbourne side Padraig Pearse’s.

The standard was good even if there were a few tough nuts and a need to keep your wits about you in games. Late tackles were plentiful.

He shared a pitch with Anthony Tohill, Brian and Jim Stynes, the three playing in secret while mixing it with AFL.

While in Australia, Corvan watched both of Armagh’s All-Ireland successes. In 2002 he looked on in a packed pub in Melbourne as the Orchard County made the breakthrough.

“In ‘24, we were in the outback, in the absolute back of nowhere, in Barkly Station,” he said of the second coming of Sam.

“It was two o’clock in the morning, in the middle of a campground in the middle of nowhere but it still felt wonderful.”

Australia is very much home now. Johnny and Ursula live in the beachfront suburb of Brighton.

Their son Sean played AFL before parking it for a decade in the Navy. Their daughter Orlagh played badminton for Victoria. Both live within a 30-minute drive around the coast and they see their grandkids often.

Johnny and Ursula stayed with her sister Mary when they arrived initially, somewhere to allow themselves to get their bearings. Johnny’s brother and sister, also in Australia, live in New South Wales.

“We were here in the last week of November and the soccer pre-season started January,” Corvan said of those early 1987 days and how sport helped them integrate.

“The players and their families all arrived from Ireland, Scotland and England at the same time.

“It became a really, really good social hub for all of us. The soccer really helped us settle and it was the same when I started to play a bit of Gaelic.”

Having been inducted in the Harps’ Hall of Fame back home, it has prompted a delve into the past. That’s what nostalgia does. History never forgets.

“There was an enormous amount of enjoyment in it and, yes, there’s probably disappointments,” Corvan said of his career.

“I played for fun and probably didn’t commit to it as much as I could have or should have in terms of training and being diligent,” he admitted. “We probably should have won a few more things but didn’t.

“There’s one thing that really sits above all else for me. I was home last year and could see the supporters, the joy that they get out of it when the team does well.

“I can probably say that I feel really proud that people have come and watched me play.

“Bringing that sort of enjoyment to people over the years is something that was not first and foremost in my consciousness, but it was important.”

Corvan admits to having fallen in and out of love for the game but today’s more enjoyable and freer version brings more joy.

“There wasn’t a lot of protection,” he said of his playing days. “You were thumped to the ground, someone could be putting the boot into you on the ground and the two umpires are standing there going ‘Oh, I didn’t see anything.’

“Those things unfortunately happened way too often but the game is in a better place because that’s not there today.”

That said, there was always the delightful side and he thanks his lucky stars to have had a ringside seat to watch some of the game’s greatest players.

“You were gracing the park with the Frank McGuigans and the Matt Connors of this world, men like Pat Spillane and Tim Kennelly.

“It was a pleasure to have the Gaelic football career that I had and I got a lot of enjoyment out of it.

“I also got to meet some of the best people that ever played the game, it was fantastic to see.”

Melbourne and Windmill are on opposite sides of the globe but Johnny Corvan will always be a Harps man. Armagh fans will always be able to delve into the extent of his magic.

When Kieran McGeeney’s side step onto their latest championship rollercoaster, Corvan will be tuned in, watching every move and kicking every ball. Once a baller, always a baller.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere