Bernard Flynn and Manus Boyle were at opposite ends of the field when Donegal and Meath last met in an All-Ireland semi-final, in 1990. Both wore the number 15 jersey and scored goals. They spoke with Michael McMullan

DESPITE bagging two goals, Bernard Flynn’s takeaway from the 1990 All-Ireland semi-final was Donegal’s physicality.

The hits dished out was a topic of discussion among the Meath players afterwards.

And that’s saying something.

The Royals knew how to handle themselves. They had tussles with Dublin in Leinster and three All-Ireland finals with Cork, including the 1988 drawn decider.

Meath club football was nowhere for the feint hearted. Then there was county training itself. Softness was a threat to success and there was nowhere to hide.

The following year, before the Dublin four-game saga, Mick Lyons questioned the temperature before deciding to turn it up a few notches. Flynn shipped a few belts before getting even, he later told Kieran Shannon, in a Sunday Tribune interview.

Flynn opened Lyons’ nose and spent the rest of the session waiting for more retribution.

“‘That’s the sort of stuff we f***n’ need,’” Lyons told a relieved Flynn in the Páirc Tailteann showers afterwards, with his arm around his shoulder, the blood mixed with shampoo at his feet.

Back to 1990 and Donegal in Croke Park, Flynn took a belt off Martin Gavigan that broke his sternum, curtailing his preparations for another joust with Cork in the final.

Flynn holds no grudges. It was football. It was inside the white lines. By November, he edged Wicklow’s Kevin O’Brien as Ireland’s top scorer in the Compromise Rules Series over the Aussies in Australia.

Robbie O’Malley, who marked Manus Boyle in August’s Croke Park clash, was Ireland’s captain. Gavigan was vice-captain.

“You can ask any man, the way that man led, the way he played out there, was just phenomenal,” Flynn said of Gavigan, who would be at the front of the queue to stand up for any Irish player if the Aussies fancied starting a row.

“I had massive regard for him. When I went on tour with him, to see what he stood for as a human being, he was just absolutely brilliant.”

Flynn and Manus Boyle both mention the wet and slippy conditions in Croke Park as Meath ran out 3-9 to 1-7 winners.

Donegal, by Flynn’s admission, didn’t get the bounce of the ball on occasions and Meath were coming off the back of winning two All-Irelands.

The Royals’ first goal needed a slice of luck. Flynn’s low shot came off the butt of Gary Walsh’s right-hand post before hitting the Donegal ‘keeper on the back of the head and into the net.

Just before half time, Manus Boyle latched on to a long ball from Declan Bonner before being fouled. He stopped up to take the penalty himself.

“I slipped,” Boyle admits about his run up, 35 years later. “I always went low and left. I knew he (goalkeeper Donal Smyth) would know that. He got his hand on it, but I hit it well enough and low enough that he was going to have to get exceptional touch on it.”

The sides were level at half-time but goals from Brian Stafford and Flynn again pushed Meath to victory.

There was a half chance for a Donegal goal blocked in the square by Kevin Foley. Stafford had a penalty saved by Walsh but it was irrelevant. Meath had the job done.

“We couldn’t believe how strong and physical they were on the day,” Flynn recalls of discussions after the game.

Sean Boylan had his homework done on the Donegal key players and what they’d offer. There was also the league quarter-final earlier that year in Clones when two David Beggy goals sunk a previously in control Donegal.

They were forewarned about the quality but just didn’t expect the extent of the physical stakes.

If anything, standing up against Meath, in Flynn’s eyes, may have taken away from Donegal’s footballing ability but leaving Croke Park he was convinced the Ulster champions were in the Sam Maguire conversation.

“I said this Donegal team is going to come,” he recalls. “I honestly believed after that day, they would come in the next year or two, and they did.

“Even our more experienced season campaigners after the game, every one of them were sore after the game. That’s the truth.”

Meath were in the form of their life in 1989, chasing a third successive All-Ireland. There was enough belief for Flynn to postpone his wedding until October but Dublin ended their hopes in the Leinster final.

After beating Donegal in 1990, Cork eventually got the measure of Meath in the final but Flynn insists the semi-final win had taken its toll.

“That Donegal game took more out of that Meath team,” Flynn said. “I have to truthfully say it on reflection. A lot of our guys had been around the block; it sapped an awful lot of our lads.”

Boylan was treating Flynn’s sternum up until the final and Liam Harnan was also suffering going into it.

More than that, Donegal had top quality players, a top manager and came to Croke Park with plenty of questions for the favourites.

“Matt Gallagher was a serious, tight operator,” Flynn said of his marker.

“I didn’t get that many possessions in that game. To win the ball that day, against the Donegal defence, was literally nearly impossible. They were on their toes.”

Outside of football, there was a respect. Flynn and Charlie Mulgrew’s paths would cross through work. He also got to know Martin McHugh through their time with RTÉ.

“One thing with the Donegal boys, when we met them at the All-Stars or at different times, they just loved their football,” Flynn added.

“The love and affection they had for football was infectious and the respect they had when they met fellow players like us.”

There would be chat and a few pints. Flynn can still remember taking his girlfriend Madeline, now his wife, with him when he was presenting medals in Killybegs after winning the 1987 All-Ireland. A couple of great days’ craic.

“It was great that they won an All-Ireland afterwards because they had a brilliant bunch of players,” he said of that Donegal group.

“Like us, when they won the All-Ireland, a lot of the players were getting over the hill a little bit. If they’d won one earlier, they probably wouldn’t have won another one.”

***

WITHOUT 1990, Manus Boyle doesn’t think 1992 would’ve happened for Donegal.

He can remember the feeling at half-time when his stoppage time penalty levelled their 1990 semi-final with Meath. They could still do it.

Fast-forward to their three-point interval lead against Dublin in the ’92 final. They were already doing it with another 35 minutes to keep repeating the dose.

“We were good in Ulster that year,” Boyle said of 1990. “We played well at times, we played a good Armagh side in the final and we played a good Derry side, who the majority of them went on to win in ‘93.”

The scoreline didn’t reflect what Donegal brought for 40 minutes in 1990. Flynn’s second goal arrived after the ship had sailed. Donegal passed up a few chances and didn’t reach the required level.

“It was probably a learning process, but it was still disappointing,” Boyle said.

“When you get to Croke Park, there had to be more running, you had to be more athletic.”

Down then ran Donegal off the pitch in the 1991 Ulster final and Boyle highlighted Meath’s runners in 1990. Beggy was a flier. Martin O’Connell could get up and down the pitch.

By contrast, Donegal’s defence – as also pointed out by Flynn – were tough to crack but there weren’t the overlaps coming out to support the ball.

That was Donegal’s learning. When they lost John Cunningham to a sending off in the 1992 Ulster final, they still were still able to run Derry ragged.

Donegal then stepped up their efforts again in the weeks before the All-Ireland series.

Where Ulster was a slog, Croke Park was open season and fresh teams. Skill was one aspect but, in Boyle’s eyes, covering the grass was king.

“When you get to that stage, you need everybody flowing between 70 and 80 per cent, and you need one or two men just dinging like Seán O’Shea (against Armagh),” Boyle said of the Croke Park ingredients.

“David Clifford as well and Gavin White coming from (number) six,” he added of Kerry’s recent quarter-final win.

“If you look at our ‘92 final, all lads played very well on the day and that’s what you need,” Boyle added in comparison.

“You must have five or six lads to really play between 80 and 100 per cent and you need everybody else then to be between 75 and 85.”

That was the Donegal difference in the two years after their 1990 Meath benchmark.

By 1992, Matt Gallagher and Martin Gavigan were the anchors and everyone else was able to carry the fight.

There was also a more clinical edge as Donegal headed on their All-Ireland winning season.

They had managed to edge a point ahead of Meath in the ’90 semi-final but Brian Murray’s low percentage show went wide.

“I wouldn’t blame him for having to go, that’s not what I’m saying,” Boyle quickly stresses, admitting it took six months before he sat down to watch their Meath defeat.

To get to the next level, these are the areas for improvement. One extra pass. Is there a goal on? A more ruthless approach and it’s a different result.

Boyle now has his coaching hat on and is an analyst on the games with Ocean FM.

“You think back and maybe we should have won more or we should have got to more finals or whatever,” adds Boyle, very much a thinker.

“Everything can turn in a minute. Everything can turn on the kick of a ball or a good save or an exceptional point or a wide.

“Momentum changes very quickly when you’re out there and it’s easy to reflect and say what could’ve been if we had more confidence in ourselves.”

Boyle feels the men of ’92 helped pass the belief down the generations where success is both now expected and should be strived for.

“I played until ’98,” he said. “We never allowed anybody, even the manager, to say we’re second best.

“Ulster football has been looked down on for such a long, long time. We have two Ulster teams in the All-Ireland semi-finals.

“It used to always be Kerry or Dublin. Galway might be thrown into it, but us in Ulster, we were always the bridesmaids.”

Boyle uses the example of Down. Their 1994 team would’ve had more belief than ’91. They weren’t coming home without Sam. It fed into Derry and Donegal.

Donegal’s training after the 1992 Ulster final put more running in the legs. They remembered 1990. At half-time against Meath, there was a chance. Nothing more.

“Was that the same belief we had when we ran in at half-time against Dublin in 92?” Boyle asks.

“I don’t think it was. I just think we learned such an awful lot from 1990 and when we got to that stage again, that we weren’t going to let it pass us by.”

Sunday marks 35 years since Donegal and Meath danced together on All-Ireland semi-final day.

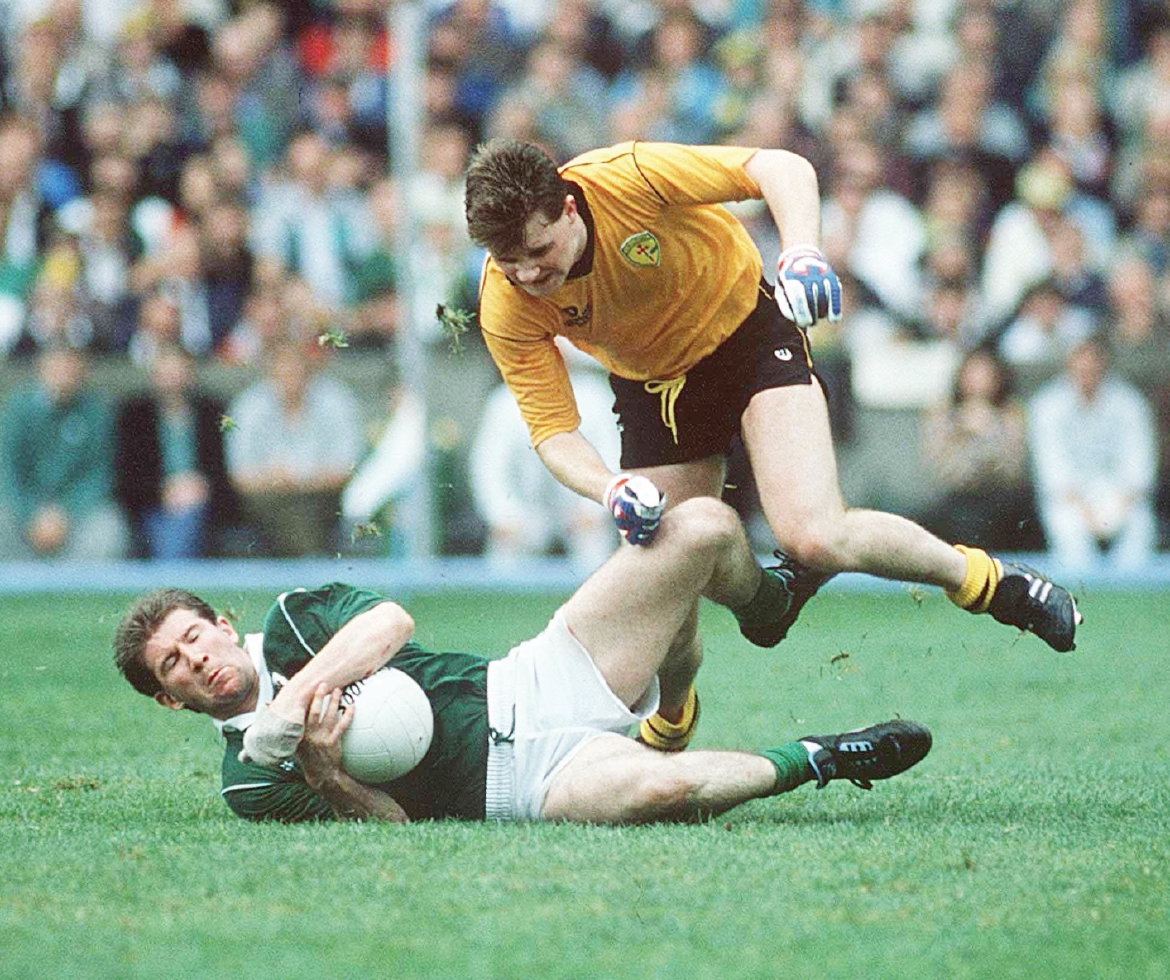

So much has changed. Croke Park. The rules. Even the jerseys. With the clash of colours, Donegal wore Ulster yellow and Meath were in Leinster green all those years ago.

Donegal will be in white this weekend. Meath in yellow.

Donegal are looking to make up for last year’s defeat to Galway.

They are further down the line. Meath, like Donegal in 1990, are the new kids. Flynn uses the word bonus territory. The prize for the winner is a seventh new face on final day in the last five years with the chance to become a fifth different champion in as many years.

Boyle and Flynn, goalscorers 35 years ago, are now powerless. On the outside looking in. The baton has been passed on.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere