“The men of ’86,

who ignited a flame that’s still burning.”

– Peter Canavan, September 2003

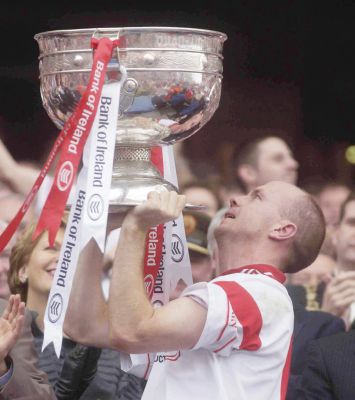

PETER Canavan never forgot the men of ’86 in the county’s greatest hour. After hoisting the Sam Maguire Cup aloft in 2003, the Tyrone skipper delivered his iconic speech.

They’ve won another three All-Ireland titles since but there will only ever be one first time.

Art McRory and Eugene McKenna were mentioned for their input. Mickey Harte and his management team for applying the finishing touch. The past players he’d soldiered with; the success was for them too.

He mentioned the men of ’86, the flame ignited by getting to an All-Ireland final and doing everything only win against Mick O’Dywer’s golden generation.

The journey nearly didn’t happen. A Damian Cassidy goal looked to have shot Derry to victory on the first championship Sunday of the season. Noel McGinn had other ideas.

“I remember Art had moved me from centre back to centre half-forward,” he recalls.

“Cassidy scored a goal but the next thing, I had the ball in my hand. I took three steps and, bang, I think it ended up in the top corner.”

McGinn jokes about it being a misplaced pass. He also recalls a punter later telling him how the goal earned him a few bob in a bet with a fellow Loughshore man, a Derry man across the Ballinderry river.

More importantly, Tyrone were on the way to Clones and then Croker. Stephen Rice had scored Tyrone’s first goal against Derry and he hit another two on the way to a semi-final victory over Cavan.

When Down’s Pat Donnan stepped back over the line, after catching a Plunkett Donaghy shot in the Ulster final, umpires awarded a goal that broke the game.

McGinn drilled over a second-half 45 into Hill 16 as they pulled Galway all the way to the closing minutes of the All-Ireland semi-final.

The game changed when Damian O’Hagan was fouled and Kevin McCabe’s penalty sent Tyrone clear with five to play before an insurance point from Eugene McKenna.

Cue the five weeks of bedlam ahead of the final with Kerry.

“It’s one of the things that the kids in school miss out on because every school in the county was visited by players,” McGinn recalls of the buzz right across Tyrone.

“Suddenly there was a media interest and huge numbers were coming to watch us. Big Art, God rest him, had a big job trying to keep people’s feet on the ground.”

There was hardly a night at training where there wasn’t a camera or a reporter.

Players were interviewed at work, on building sites, in offices and McGinn can still remember Peadar O’Brien coming to interview him as he taught in school.

All of a sudden, sponsors came forward and the team was provided gear as the plans for the final ramped up. The players all received a pair of boots and McGinn still has his All-Ireland final kitbag tucked away in attic.

“We had no experience of that type of interest,” he said, referencing how it was only Armagh in 1977 that reached a final since Down’s glory days of the 1960s.

It was different in Kerry where O’Dwyer was negotiating kit deals with Adidas and topping up the players’ fund from the benefits of a Bendix washing machine endorsement.

This hype was all new in Tyrone and the All-Ireland breakthrough elevated the players’ status. Gaelic games became even more popular.

It was common enough for a player stepping up to square a bill in a restaurant only to find someone had recognised them and quietly settled up beforehand.

While Tyrone and Kerry were coming from different places in terms of big day experience, the Red Hands showed no signs of stage fright.

Some newcomers get blinded by the bright lights but Tyrone tore into Kerry.

They survived a scare when the often-referenced Canal End curse of penalty takers struck Kerry when Jack O’Shea’s rasper crashed off the crossbar.

Sean McNally was running amok, kicking points off either foot, and Kerry were in real bother.

A second-half goal from Paudge Quinn shot them into a six-point lead. Kerry were rocking but breathed a sigh of relief when the Canal End curse then hit Tyrone, as McCabe’s penalty flashed over the bar.

It gave Kerry hope with Ger Power then making goals for Pat Spillane and Mikey Sheehy as the champions strode to a third successive title.

“We didn’t feel that we had any inferiority complex against Kerry,” McGinn said of how they hit the ground running.

They’d both drawn and beaten Kerry on occasions and in McRory, they had a man who was ahead of his time.

“Art had such an influence on that team,” McGinn said of his former manager. “He knew how important it was to build from the base up, on the solid foundations of successful youth teams.

“He was always a big, big believer in how important winning became as a habit and the psychological influence of it. It could change you from being run of the mill to being a potential champion.

“He had a three-year plan that was to culminate with an All-Ireland title in ‘86,” McGinn points out.

“He sat down with us and spoke about it was going to pan out, but he hadn’t factored in Frank McGuigan’s injury or car accident.”

McGuigan was the genius that won an Ulster final literally by himself two years earlier and is rightly lauded as one of the greatest players to have donned the Tyrone jersey.

“I still maintain, to this day, if Frank hadn’t had the accident that he had, we would have beaten Kerry, I have no doubt about it at all,” McGinn says with utter conviction.

He came into the senior setup with John Lynch from the minor teams of 1978 and 1979. McRory had them as u-21s before calling them into the senior ranks.

McGinn made his debut, coming on as a sub to help defeat Meath up in Pomeroy in a refixed league game in 1981, when the weather had said no before Christmas.

Winning Ulster in 1984 was a learning experience for the group.

“We got a feel for what it could be like and how close we came but things didn’t work out the following years (after ‘86),” McGinn said.

“If we had been able to win the next couple of Ulsters, we probably would have won the All-Ireland,” he surmises.

“You can take the lessons from the experiences that you had and build on it. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to do that.”

After Stephen Conway’s monster free earned another Ulster success in a replay win over Donegal in 1989, defeat to Mayo in the All-Ireland semi-final was the end of the line.

A new batch of players from successful All-Ireland u-21 winning teams backboned the next generation, the team who were controversially edged out by Dublin in 1995 with Sam Maguire in sight.

By that time, Harte was beavering away at minor level, bringing through a batch of starlets that stood on the steps with Canavan when uttered the final words of his 2003 All-Ireland final speech.

“I think I’ve said enough, it’s time to take Sam to Tyrone,” Canavan bellowed.

So, what was the legacy of 1986? What was it like to be standing in Croke Park when the first ever winning captain remembered the men who, 17 years earlier, were the first to run out on the season’s biggest Sunday?

“It’s hard to know,” McGinn said, “but it was nice to be mentioned because they were a great bunch of lads, some brilliant players.

“O’Hagan, McCabe and McKenna and these guys were household names. They were not just among the best in Tyrone, but the best in Ireland, they really were fabulous, fabulous players.

“They were great people and I mean, great people. They were absolutely brilliant, brilliant men.

“The sort of guys that would dig you out of a hole, boys like Joe Mallon. There’s always one or two characters. There was always one or two stories told and maybe one or two lies,” McGinn continued.

“For all the size of him, Joe was nearly as broad as he was high. Joe was one of these guys who trained as he played. When he went for the ball, it didn’t matter if there were two or three men in front of him, Joe went for it.”

Fast-forward to now and McGinn, in his role with Team Talk Mag, can see the picture from the other side of the line. Be it school, club or county, he’ll rock up to report on all things Tyrone.

It’s changed times since 1986 and Peadar O’Brien perched at the back of his classroom, but the mantra is still the same. Promotion of the games.

“Football improved remarkably,” McGinn said of the change, adding how 1986 saw numbers grow within club coaching structures.

“Businesses took an interest in it, sponsorship came into it and money came into it,” he added.

“A few wise men around Tyrone looked at ways of funding. They knew that if we were going to make the breakthrough, that it was going to take money,” he explains of how the buildup to the 1986 final had snowballed.

“All we got at the end of it was a pint of milk and maybe two or three chocolate biscuits,” he recalls of his early playing days. When they began to train in Augher, there would be tea and sandwiches.

“God rest John Rice; he was a marvellous GAA man. There was a kitchen there, John and his wife Kathleen were able to make us tea and sandwiches.”

It warmed the system and provided vital sustenance before the players trekked for home, or, in some cases, up the road to a student haven in Belfast.

A fundraising venture for the 1995 team grew into a five-year millennium project that eventually morphed into the Club Tyrone of today.

It hasn’t stood still. Tyrone GAA are currently advertising for a fundraising and business development executive – or executives – to drive funding in the county to the next level.

Looking back to 1986, Adrian Logan was just coming on the scene in the media landscape.

Logan’s local knowledge helped him grow the profile of football in the county at a time when just three games would’ve been televised live in the season.

McGinn can recall days out shopping, mixing with both sides of the community and their awareness of what Tyrone were doing.

One person asked about Sean McNally’s credentials, expressing how he’d have been at home in any professional sporting environment.

Having grown up, McGinn can recall watching Patsy Kerlin in action. After the wilderness of the 1960s, the seventies brought success back again.

“I went to all those matches, that’s when I started to follow Tyrone in a big way,” he said.

“People sometimes forget just how good the ‘70s were and a lot of that was down to Art.

“He trained the minor and the vocational school teams. When those teams were going well, we always hoped that eventually it would lead to success.”

The men of ’86 benefited and grew into the first group to get within touching distance of the biggest prize the sport can offer.

“We were close but just not close enough. Our lack of experience probably cost us.

“When you look at what happened from that, sometimes it’s the story of the ripple from the stone in the water. You just don’t know where the ripples end.

“The ‘86 team, they lit a fire. They aroused the interest of people from all walks and all parts of the county.

“It opened doors and shone a light into places there hadn’t been light before. Then, Mickey (Harte) and his teams came along and all the success they had, which was amazing.”

McGinn’s only regret – it was a level of success that came 15 or 20 years too late.

Every few weeks, McGinn and John Lynch meet for a cuppa and a chat. They sat side by side in the All-Ireland photograph in 1986. Their friendship remains.

Canavan never forgot them or the rest of the men who ran out of the old Croke Park dressing rooms, facing into Hill 16, the sea of red and a wall of deafening noise.

They ploughed a field that yielded four of the most glorious summers Tyrone will ever remember. They’ll hope the men of now can make it a fifth.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere