Fionn Fitzgerald is an All-Ireland winner with club and county. He is currently a PhD student looking at growth and maturation in Gaelic football. He spoke with Michael McMullan…

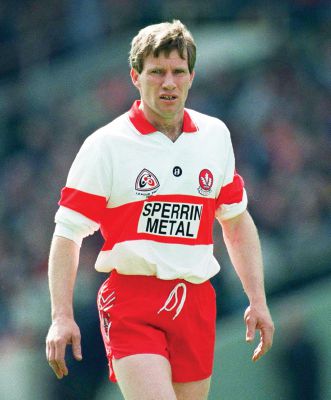

THERE are four All-Star awards on the top of Tony Scullion’s cabinet at his Ballinascreen home. He is an All-Ireland winner. An Oakleaf icon.

Alongside Martin McQuillan, he played every minute for Ulster’s Railway Cup team during their six-in-a-row. He starred for Ireland in the International Rules.

Scullion is one of the game’s famed late developers, deemed too small to even be sent to a Derry minor trial.

Everyone will have their own example that springs to mind. Fionn Fitzgerald see himself as one.

Alongside Kieran O’Leary, they lifted Sam Maguire as joint captains in 2014. The pair were part of the Dr Croke’s team that walked up the same Hogan Stand steps three years later.

Fitzgerald has spent the guts of five years poring over the facts and figures of who comes through from Kerry underage academy squads. And over who gets selected.

A lecturer in MTU Kerry, he also owns Kaipara Academy that operates out of Fitzgerald Stadium in Killarney. Its focus is on underage athletic development.

Chatting to Gaelic Life last week, he was applying the finishing touches to his study into growth and maturation as part of a part-time PhD via University of Limerick.

His motivation for digging deep? It’s based on two things. One was an initial study on relative age for his undergraduate studies. How those born earlier in the year have a greater chance of selection.

The second was his own sporting experience. Despite being born in April, deemed in the ‘good birthday’ range, he matured late.

LATE BLOOMER…Tony Scullion never played minor for Derry

After struggling to make the younger St Brendan’s, Killarney school teams on his way up, he played the school’s 2008 senior team that won the Corn Uí Mhuirí in Munster before losing to Sunday’s MacRory Cup finalists St Patrick’s, Dungannon in the Hogan Cup final.

Also on the ‘Sem’ team were future Kerry players Brian Kelly, Johnathan Lyne and 2014 player of the year James O’Donoghue.

By the summer of ‘08, all four were on the Kerry minor team, a crop that also included Peter Crowley, Paul Geaney, and Barry John Keane. They lost an All-Ireland semi-final replay to Mayo who in turn lost to Tyrone after a replayed final.

The Tyrone team included Mattie Donnelly, Peter Harte and Kyle Coney. Aidan O’Shea, Rob Hennelly and Kevin Keane would graduate to the Mayo seniors.

That was Fitzgerald’s fleeting taste of Kerry until his six-year senior career began in 2013. In that lies his second layer of motivation for his current study.

“I suppose realistically a lot of it was formed from my own underage career,” he begins.

“I would have been a smaller player and would have had to, I suppose, adapt my gameplay into a bit more of a skill-based, evasion type of game.

“Then I wanted to delve into the kind of growth side of it a little bit more,” he continued on his motivation to dig deeper into player development.

At some of his presentations, Fitzgerald has thrown up a photograph from a Kilcar underage game. Two players feature, Patrick McBrearty and the eight-month younger Ryan McHugh. McBrearty looked 16. McHugh looked 12.

Both were taken into the Donegal senior team as soon as their minor days were gone.

They walked alongside Fitzgerald, behind the Artane Boys’ Band, on All-Ireland final day in 2014. From their pen pics in the programme, McHugh was two stone lighter and four inches shorter than his clubmate.

McHugh was a special minor talent but many players of his stature would’ve been brushed aside by the monster bulldozing through a county academy trial game. Gone and forgotten. Their potential completely unknown.

The same presentation had a photo of a young Roy Keane, tiny alongside his teammates. How many coaches would’ve missed a Ryan McHugh or a Roy Keane?

“You had players who came along late from minor onwards in particular,” Fitzgerald said of the players he grew up alongside in Kerry.

“Then those who really stood out to me at, u-14 or u-16 for example, struggled then to make it to even senior club level.”

It struck a chord with Fitzgerald. He wanted to look under the bonnet and see what was really happening.

His undergraduate study was based around punching in nearly four thousand dates of birth from various underage development squads.

Similar to other sports, GAA squads were littered with players born earlier in the year. It was time to look deeper at the real difference.

*****

Rather than height and age, maturation is a truer key term when really looking into both a person’s development and potential.

Maturity kicks in with puberty and development rates differ with everyone.

Fitzgerald’s new best friend became the Khamis Roche approach to estimating a young player’s height as an adult. Calculations are based on gender, current height and weight, coupled with the height of both parents.

“We can estimate where players are at in their stage of physical development, in other words, what their final adult height will be,” he said.

“When we work back from that, we found that there’s a far stronger influence from a maturity point than from relative age.

“In our studies, some of the actual younger players actually may be more mature from a physical perspective and vice versa.”

The data also looks into growth spurts, both in terms of height and how players actually fill out. There is also the factor of how quickly both can happen.

For boys it’s between the ages of 13 and 14, a year later than girls.

It’s something coaches must be au fait with. Rapid growth leads to imbalance which then brings both injury and a loss in coordination.

The difficult part is how a growth spurt mostly falls during the teenage years when players are trying out for development squads.

“Coordination potentially might be affected, performance levels might drop for that period of time because there’s such a such a big impact from the point of view of that accelerated growth spurt,” Fitzgerald said about looking beyond what the eyes can see. A study of core numbers.

“The analogy you sometimes use for parents, it’s almost like they’re driving a Nissan Micra at 13 and, all of a sudden, within a year, they’re driving a Ferrari, but they just don’t know how to drive it.”

Consideration is also needed to the differences between male and females’ growth patterns.

“Generally, between roughly 85 and 95 per cent of someone’s predicted adult height, that’s when they’re going through their growth spurt,” Fitzgerald clarifies.

A player at 90 per cent is then bang on the middle. Fitzgerald’s research across Kerry and Cork academy squads flags up as much as a 15cm growth over a year or adding up to two stone of lean muscle.

The changes can even be significant even over a number of months. There are evident signs like growing out of clothes and shoes.

For a typical club coach, keeping a lid on this can be off-putting. It’s not really. A spreadsheet, populated with the parents’ heights, can be updated at intervals during the season with the new player data.

“You are just identifying players, it could be five players that might be in the what we call the ‘red zone’ for that period of time,” Fitzgerald explains of the window for growth.

“There will be late maturing players and then on the flip side, at the other end of the spectrum, we had 13 year olds who are at 100 per cent of adult height, practically like grown men.”

Fitzgerald’s study also has a photo of two u-14s from his findings in Kerry. It was similar to the early McHugh v McBrearty reference.

The player at 89 per cent of their expected height of 172cm had a biological age of 13.1. The other, practically nearly at their expected height of 170cm, had a biological age of 17.5.

Think about that. Essentially that’s a player in their first-year u-14 coming up against someone in their final year of minor, something the GAA have since ruled out.

We’ve all watched examples of the man child taking a kick-out without needing to jump, before running through, tunnel vision, to hammer the ball to the net.

Unless there is a two-touch stipulation, there is no challenge for the big player on the ball or for the smaller gasán who’ll rarely get a touch. It’s a game but it’s not really a game.

This is where Fitzgerald’s interesting study of bio banding comes in. He uses samples from Kerry North and Kerry South academy squads.

Within both squads, the players at more than 94 per cent of their expected height trained together with the “less mature” players doing likewise in a different group.

Over a month, they used small-sided games before then having one game across both squads.

The “more mature” group was divided into two teams. It was the same for the early maturing players.

The results were intriguingly simple. The bigger players, previously used to having their own way, realised they now needed decision=making qualities, skill, evasion and had to take others into the play. There was no tunnel vision because there was no tunnel, rather a wall of defenders the same size.

The smaller players, playing against a similar physique, got more possession of the ball and coaches got to see a repertoire of skills not previously evident.

The big players needed to make space their friend. Power replaced by awareness. The smaller players got a chance to express what they had. Both types of player had a chance to develop different, yet important, footballing dimensions.

Think back to Ryan McHugh and the 2014 All-Ireland parade. Four inches shorter than Patrick McBrearty wasn’t the end game. The damage he did when Jim McGuinness pressed up on the previous infallible Stephen Cluxton. McHugh’s runs the kryptonite to quell the Dubs on the way to the final. Absolute proof that size doesn’t always matter.

McGuinness saw beyond McHugh’s slight body at minor level on a Donegal team that didn’t even reach an Ulster final.

Winning isn’t everything at underage level. We all want it but the sole purpose, in forward thinking counties, is getting the correct type of player through.

The minor team Fitzgerald played on, that didn’t win the minor All-Ireland, had seven future seniors on it. A savage return. More than most.

One of the players, O’Donoghue, has always maintained losing at minor level only sharpened a pencil underage success can often blunt.

MAKING HIS MARK…Mark O’Shea made his Kerry debut at 26

The other side of the coin is the late developer. Unlike Fitzgerald, his clubmate Mark O’Shea never played with Kerry at all until his senior breakthrough last year.

In the face of a midfield injury crisis, at the age of 26, he became the athletic battering ram they needed with the football to also take him along.

“He would have been someone who I remember when he was very young,” Fitzgerald recalls.

“He had all the skills but he was tiny, absolutely tiny. Mark was a really, really late developer.

“Generally, we say a boy, on average, goes through their growth spurt around 13 and a half or 14 years of age. For some, it can be 11 if they’re very early advancing and a late maturer might go through it at 15.

“Mark was maybe 16 or 17 when he went through his big growth spurt. He was nearly struggling to make the club team towards the end.”

While others were growing without around him, O’Shea spent time working on skills, game awareness and decision making. Add in his basketball and there was a late developer waiting on the call.

Jack O’Connor punched in his number and, hey presto, he was one of the giants that boxed All-Ireland champions Armagh into a red hot, 15-minute, pressure cooker they couldn’t handle. He never looked back.

“It took him a while for him to grow into that new body,” Fitzgerald said. “All of a sudden, over the space of a few years, he really physically developed. He went from a wing-back or corner-forward, he must have played everywhere really to eventually end up at midfield.

“It wasn’t like he was midfield all the way up, but had a lot of the skills developed from having to play around the place and he worked around his limitations.”

In Fitzgerald’s ideal world, every county would run their games programmes as they usually do.

Alongside it, each team would have a spreadsheet of their players’ estimated adult height with their percentage of how close to it their current height it is. There is a better chance of training load or injury management. Knowledge is king.

Once a month, there would coaching or games with a difference. Where the big man is forced to look up and deliver a kick pass forward. Likewise, the scoring assassin will make a dummy run before crisscrossing, knowing he’ll get a kick pass delivered with one bounce. Perfect to run on to. And, bang, over the bar.

When they go back to the normal games, both players can now actually see each other. More importantly, the coach can develop a gameplan that marries both.

Players like Mark O’Shea and Tony Scullion are in the minority, the All-Ireland winner who takes a more scenic route to the steps of the Hogan Stand. There is an element of luck. The right place at the right time.

Imagine a scenario where GAA coaches spend as much time looking for the hidden gems that they are not actually hidden any more.

One thing remains. Getting players through from minor every year is gold. Fionn Fitzgerald’s plan to replace gut instinct with something measurable has value. Is it any wonder Kerry are always winning All-Irelands. They never stand still.

Fionn is a lecturer in MTU Kerry and owner of the Kaipara Academy. Full interview on this week’s Gaelic Lives podcast, now available on Spotify and YouTube

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere