I INTERVIEWED David Gough at the weekend, our greatest referee. He supports my four new rules.

Q. The sweeper is the real game killer?

A. It is. It has become an awful boring game to watch Joe. Even to referee. It is dreadful. I wouldn’t go to watch a football match now and I used to love football before the sweepers and blanket defences came along.

Q. You wouldn’t watch a game at all?

A. Well, I would watch Dublin v Kerry. And the Aussie Rules is great.

Q. That’s because they banned the sweeper and zonal defending.

A. It’s a brilliant game now.

Q. Some people have said that my proposed rule that bans the sweeper inside the 40 metre exclusion zone is difficult to police.

A. Nonsense. A sweeper is dead easy to see. Even a referee alone in a club league game can see the sweeper straightaway. They stand out a mile. I’ve no problem with that rule, it would be very easy to police.

And there you have it. As Jimmy Cricket was wont to say, “there’s more.”

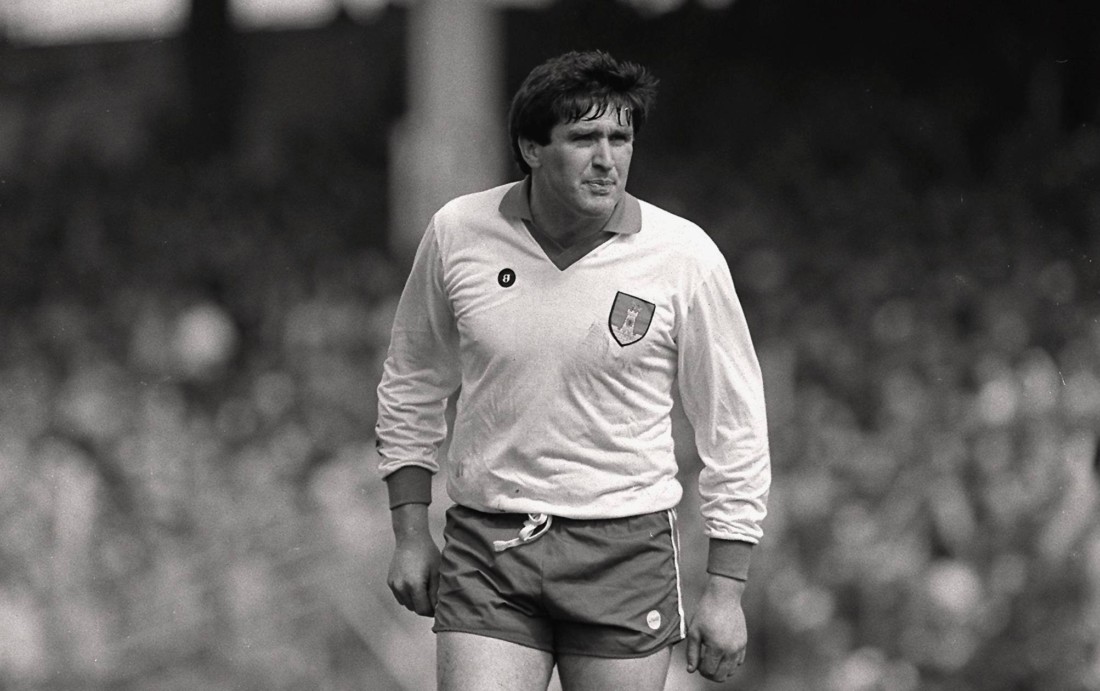

The night before, I bumped into Pat McEneaney, the greatest referee of the previous generation. He was in Croke Park for Garth Brooks. Pat Gilroy and me went into Banty’s box to say hullo. The place was bouncing, like a US marine bar in Hanoi. The only man not wearing a cowboy hat was Gerry McCarville. Gerry doesn’t need to wear a hat to cut out a bit of respect. Part of the fearsome Monaghan full back line from the late 70s and 80s that could have won an All-Ireland (Kerry beat them in a replay after a rivetting two game series). It was great to see him looking so well. When he shook hands with me, my hand disappeared.

Pat came over to me. “Brother,” he said, “I fully agree with your rule proposals. The game has gone awful bad.”

When is the Rules Committee going to act?

In the NBA, they had the same problems. By the 70s, the game had been hijacked by the coaches. Holding possession endlessly, killing the game, zonal defending, cynical fouling. TV audiences collapsed. Stadia were half empty. They stopped showing live games and started running them as repeats late at night. Then, the ruling body began to ruthlessly change the rules to enforce a spectacle. To enforce contests. Suddenly, entertainment returned. Just as well they did. On the 11th of August 1959, an atom bomb of charisma was dropped on America.

Fifteen years later, in his second High School game, under the freedom of the new rules, the bomb posted 36 points, 15 assists and 10 steals. After the game, an enthralled sportswriter from Lansing Michigan, Fred Stabley junior, went into the locker room to speak to him. “We’ve got to give you a name kid. I can’t call you Earvin…” The excited sportswriter rang a local scout and told him, “This kid will make you forget about every other basketballer you’ve ever seen.” The first line of Stabley’s immortal match report was, “Earvin ‘Magic’ Johnson sauntered over to the bench, a smile covering his youthful face and slapped hands with everyone of his team mates.” The second christening stuck. From then on, he was just ‘Magic’.

Samuel L Jackson leans back on his sofa and says, “Man, that was one mythological cat.”

For the next 20 years, he was the Pied Piper of American sport.

Magic’s son EJ, an openly gay cross dresser and an American fashion icon, says, “Magic wasn’t real. He was a superhero in a cape who played basketball like a God. In real life he was impatient and controlling and could put you through hell.” It is the schitzophrenia at the core of the greatest athletes. His desire to win (almost) obliterated everything else. In the 1988 finals, he squared off against his closest friend, the great Isiah Thomas of the Detroit Pistons. After the Lakers had lost the 1984 finals in game 7 to Larry Bird’s Celtics, Thomas had stayed with Magic in his hotel. “I sat in silence with him in his hotel room until the morning. He sobbed for literally the whole night. He was very vulnerable.” A few minutes into game 1 of the 88 finals, Magic smashed his old friend with a forearm into the throat as the smaller man drove to the basket. An ugly confrontation followed. It set the tone for the series. They didn’t speak again for years. Magic says simply, “For me, it has always been win at all costs. If it cost me friendships, then it cost me friendships.”

When he arrived into the Lakers locker room as a 19 year old, the team captain and greatest player in the league was Kareem Abdul Jabbar (also an expert in martial arts who starred with Bruce Lee in Enter the Dragon). Kareem recalls (laughing), “We could hear his boombox as he got closer to the dressing room, blasting out Parliament Funkadelic.” Coach Paul Westhead says, “I fell in love with him straightaway. Everyone fell in love with him.” Magic, laughing (he is always laughing), says, “I was doing no look passes through the legs, behind the back. Woohooooo. Aw man (he shakes his head in delight at the memory as though he were talking about someone else) it was beautiful. Woohoooo.” But he was terribly homesick, once saying, “I couldn’t get a hug from my mom anymore. Or talk to my dad.”

That was before the Lakers’ owner, Dr Jerry Buss took him under his wing, which meant two things: Money, lots of it. At the end of his rookie year, Buss signed him to a 25 year, $1M a year contract, the richest ever in world sport. And orgies. Lots of them. Before Game 6 of the finals in his rookie year, Kareem sprained his ankle and was ruled out. As they waited for the flight to Philadelphia, the atmosphere was like a morgue. Magic sauntered in, boombox blaring out Jamaica Funk, Ring My Bell and announced, “Never fear, Magic is here.” And so he was. He destroyed the Sixers in that game, becoming the youngest ever Finals’ MVP. Now, it was time to party.

Think a 6’9” Austin Powers with terrific good looks and the body of a Greek God. The documentary has clips of his pool parties, which were legendary. No wives or girlfriends allowed. Luther Vandross played at them. Magic was Ron Burgundy without the jazz flute, cannon balling into the pool. Women swooned. Men looked down, reminded of their lack of self worth.

Magic says (again as though he were talking about someone else), “I did my best to accommodate as many women as I could, mostly through unprotected sex. Women have different fantasies. Being with two or three of them at a time. One time I had six women together. If you ask me did I have fun, well yes I did.” Again, he laughs. He is always laughing.

The Runaway Groom.

He met Cookie when he arrived at college and immediately fell in love. Three times he jilted her. The funny thing is that this man who was openly going out with multiple women and putting Hugh Heffner to shame on the waterbeds of LA, bore no resemblance to the tender, loving, empathetic human being who simultaneously emerges. Weeping, Magic recalls, “My father rang me up and he says, son you better marry this woman. God help you, if you don’t, you’re going to make the biggest mistake of your life.” They had broken up again by then and Magic had fathered a son on a one night stand. So, when he rang her to ask her to marry him for a third time, she said she would only do it if they got married immediately. The wedding was set for a fortnight later (Cookie says at least the third engagement ring was bigger than the first two). She says, “I was sure he wasn’t going to turn up again. I was so scared he was going to do it again.” The magician surprised her. He turned up and the fairytale wedding between a good and faithful woman and a man with the sexual morality of an alleycat finally went ahead. Funny, it is somehow no surprise that this became a life together of love and devotion and respect. This childlike man, who talks openly about himself, concealing nothing, emerges as the least hypocritical person you will ever come across.

The documentary is, at times, intensely moving. Recalling Magic’s HIV diagnosis in 1991, his agent Lon Rosen, sitting in his office 30 years later, breaks down and weeps. Footage from the time shows Magic shortly after receiving the news (AIDs in those days was believed to be a death sentence). His beautiful face, usually lit up like Yogie Bear, is ashen and downcast. His mother describes how she went out into the family car and wept. Magic talked openly of taking his own life. There is an unbearable scene where Magic, by then a champion for AIDs patients, appears on a Nickleodeon Special with young children who have AIDs. As a small child weeps uncontrollably at the unfairness of it all, he consoles her so delicately. Just like he did with basketball, he transformed the narrative around AIDs, destigmatising it and making it mainstream, even giving press conferences from the White House with his new buddy George Bush senior.

His son EJ gets closest to the heart of this pure, emotional man. When he came out, his father was confused and angry. EJ says, “I was rocking the scarves and the clothes. He just could not stand it.” Shortly afterwards, EJ left home to study at NY University. Two months later, EJ recalls his father turning up at his dorm. “He hugged me so hard. He was like squeezing all the air out of me. I knew then there was nothing but love there.” And that was that.

In his first game for the Lakers, with two seconds to go and his team a point behind, Magic passed the ball to Kareem and the big guy won it at the buzzer with his patented sky hook.

To the amazement of his veteran team mates, Magic jumped on Kareem (a quiet, intensely serious man who meditated, and closely guarded his personal space) and initiated a pile on. Magic recalls, “I got in the locker room and Kareem was angry. He shouted at me ‘Rookie, don’t you ever do that again. We’ve got 81 more games to play.” Kareem says, “He just smiled and said, ‘If you win 81 more games this year with a shot like that, I’m gonna jump in your arms 81 more times.” What chance does reality have against magic?

He has gone on to do a million things, including building a billion dollar fortune setting up businesses in the black ghettos, investing in Starbucks, and the newest terminal at JFK airport, and funding countless community regeneration programs. He still gets up at 4am every morning. He still has that insatiable lust to win, with the ever present threat it could ruin the good life he has found. But he loves his wife and it seems clear his dad was right. This woman is the only really important investment he has ever made. As for the orgies, they are long gone now, just funny stories on a night out with the lads.

This is a story of love. More than that, it is a story of magic. If the NBA hadn’t changed the rules, we might never even have heard of him.

‘They call me Magic’. Available now on Apple+ TV.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere